I’ve now shared all code in my repo

In this blog post I will share my experience with building a BPE tokenizer from scratch, analyzing its quality, sample efficiency, and efficient implementation.

This work started as part of the excellent CS336 “LLMs from Scratch” course, but then quickly developed into its own mini-project due to my curiosity to explore things further.

Disclaimer

Algorithms presented in this blog post might not be optimal since I was never good at this, I am more a practical person that cares about efficiency as long as it improves quality. I would rather rewrite to Rust than make Python faster. This text is more like my journey into building tokenizers and achieving better sample efficiency than off-the-shelf solutions, since my end goal is ultimately achieving the best quality (or lowest loss) during LLM training.

Intro

Tokenization is needed to convert your text into numeric representation that is useful for training LLMs (and to essentially compress your data too, reducing sequence size)

Let’s discuss BPE tokenization algorithm during training:

Each string character in UTF-8 encoding is represented as bytes (values from 0 to 255). We convert text to bytes. This is our initial set of tokens.

At each step: 1. Count adjacent token pair frequencies. 2. Merge the most frequent pair into a new token ID (sequence becomes shorter). 3. Repeat until you hit your target vocab size.

Larger token ID -> later it was created from merge.

General scheme of BPE training

Byte-level BPE accepts bytes and returns sequence of ints (this can be saved as *uint16* if your vocab size is less than 65536), and no input is left un-tokenized (in contrast to earlier tokenizers which used <UNK> token for unknown tokens that don’t fit into vocab)

Single training step of BPE algorithm

Here we make a frequency count for each pair of numbers, select max pair by this count and replace it with a new token ID.

There are few nuances in the implementation.

Not all bytes are created equal

Since byte is just a number from 0 to 255, but we have much more characters than 256, we represent it with variable amount of bytes. An average English text would be 1.25 bytes/character.

- Each UTF-8 code point is represented by 1–4 bytes, depending on the character.

- ASCII (U+0000–U+007F) → 1 byte

- Latin, Cyrillic, etc. → 2 bytes

- Most CJK (Chinese/Japanese/Korean) → 3 bytes

- Rare supplementary (emoji, historic scripts) → 4 bytes

Pre-tokenization

It’s easy to show the naïve algorithm is $O(N^2)$ (or more concretely $\Theta(VN)$ for $V$ being vocab size ($≈ N^2$ if $V\propto N$))

For large files, even a single iteration becomes very computationally expensive (for 5 GB file, $N$ would be 4e9 and single step would take 100+ days on modern CPUs!)

One optimization that we could use is to split whole training corpus into words (split by token ID 32 (" “) in this example – or, more generally, by any whitespace character) and group words together via hashmap.

Then, knowing the count of each pre-token, true count for a pair of numbers becomes

frequency(pair within word) × pre-token count

It’s even better to split not just by delimiter, but by a more complicated regex. For example, this is the regex used when training GPT-2:

'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re)| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+

It splits text “Let’s consider tokenization word-by-word” like this:

['Let', "'s", ' consider', ' tokenization', ' word', '-', 'by', '-', 'word']

Notice we attach whitespace to the left.

Schematic representation of pre-tokenization

What’s SOTA in regex patterns?

Nowadays, people use better regex to handle code, long numbers or delimiters smarter.

- Digits: triad chunking with

\p{N}{1,3}; support for thousands separators (, and _), decimals, scientific notation, and percents. These help BPE learn reusable numeric chunks without exploding vocab. It also improves math benchmarks since we represent numbers more faithfully. - Contractions: handle both ASCII ’ and curly ’, case-insensitive, so “It’s”, “IT’S”, “it’s” → consistent splits.

- Punctuation: keep

[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+to group operators/emoji/punct as learned units. (this part is advanced and requires a non-regex grapheme/emoji segmenter; regex alone won’t cleanly capture all emoji families.)

In addition, when it comes to data preprocessing, there’s also a notion of special tokens that we do not split into subwords, or into bytes, i.e., they are not involved in the training. One of the most popular special token examples - end of text. It is important to keep it as it is as we use it to split documents with each other, and tell the LLM where the sequence ends, so that at inference we would have an LLM that can actually stop its generation :)

Training pipeline

Generally, now whole training pipeline looks like Pretokenization + N iterations of merges. We would explore optimization for one merge iteration step below.

Pretokenization was rewritten in Rust (via PyO3). The Rust code splits text with a regex and counts pre-tokens directly, avoiding round-tripping large Python string lists (pickle/marshalling). I used simdutf, ahash for efficient decoding and counting.

Single-process benchmark (1.5M lines):

- Baseline (Python): 67.2 s total – split: 45.6 s, count: 17.3 s

- Iter 1 (Rust split, Python count): ~26.0 s (split) + 17.3 s (count)

- Iter 2 (Rust split + count): 21.2 s total

Practical optimizations

There are still a couple of questions related to merging process:

- How to detect the most frequent pair inside a pre-token efficiently? Do we need some specific data structure?

- How to most efficiently merge two tokens together and update the list in-place?

- Is there a difference between encoding during training and during inference?

Let me answer all of those questions at once. I will share the data structures, some hacks, and the inference implementation. That might not be the best algorithm overall, but this is what I found worked for me and hopefully this can give you some food for thought.

First of all, for training our main goal is to be able to find the most frequent pair very quickly. Unfortunately there’s not much we could do to merge faster during training. We still need to linearly scan the sequence.

Let’s cache pre_token_counts, updated_pre_tokens, all_pair_counts, pair_to_pre_tokens.

all_pair_counts is the most important map. We take the top-1 count each step to get the max pair.

Two observations:

- After each update, we don’t need to re-compute

all_pair_counts. We know that most pairs are untouched, so we keep only pre-tokens that have been updated (updated_pre_tokens). Moreover, we know that frequencies of pairs change in deterministic order. So, if we had a sequence (1, 2, 3, 4) and merged (2, 3) -> 99:- Subtract counts for pairs destroyed by the merge.

- Adjust counts for pairs that touch the merged span (e.g., (1,2)→(1,99), (3,4)→(99,4)).

- Leave everything else alone.

Including these modifications lets us cache all_pair_counts and update it after each iteration instead of re-computing.

This change reduced my total training time 7x.

- We know there are situations where top-k pairs from

all_pair_countsremain the same (so top-2 becomes top-1 in the next step, and if we know that in advance, we could retrieve next max pair in O(1)). Intuitively, this can be if our updated frequencies inall_pair_countsdo not touch any of the top-k keys, or at least do not drive them too high. This is a pretty weak assumption but it helps to reduce the search space and avoid resorting keys ofall_pair_countsevery iteration.

- Cache the top 10% from the previous sorted list.

- Re-sort only pairs involving keys updated in this iteration.

- Merge the cached top-10% with the newly sorted updated pairs and take the top-K.

This reduces training time by a factor of 3x, obtaining 20x improvement over baseline.

A natural data structure for all_pair_counts is a max-heap. Updates are $O(log(N))$, and retrieving the max is $O(1)$. When I tried it, I noticed that we add/remove keys too frequently, so that the overhead of max-heap becomes too high. I keep it as a dict and try to sort elements when needed.

I wonder how these 2 optimizations change algorithmic complexity?

$P$: # unique adjacent pairs in the whole corpus ($≤ N$).

$\Delta_t$: # distinct pair keys whose counts actually change at iteration t (typically $\Delta_t \ll N$)

If we store counts in a dict and only touch changed keys, per iter update cost is $\Theta(\Delta_t)$

Over all merges, each token position can only be rewritten a constant number of times, so $\sum_t O_t = \mathcal O(N)$ and typically $\sum_t \Delta_t = \tilde{\mathcal O}(N)$

Total (amortized): $\boxed{\Theta\big(N + M\bar L + P + \sum_t \Delta_t\big)}$ -> $~O(N)$

where $M$ is total numbero of pre-tokens and $\bar L$ is mean length of a pre-token (in bytes)

- Sorting heuristic:

If we cache the top 10% from the previous sorted list, re-sort only pairs involving keys updated in this iteration

Selecting the next max now costs about $\Theta(\Delta_t \log \Delta_t)$ per iter (to re-rank only changed keys), plus an occasional refresh of the cache ($\Theta(P \log P)$ every $R$ rounds) instead of $\sum_t \Delta_t$.

In practice, this cut sorting time by ~3× with no observed quality loss in my runs.

Note: This is an approximation—there’s no strict guarantee that the true global top item won’t fall outside “updated pairs + cached top-10%”.

I suspect we could go even further and employ probabilistic algorithms, Bucketed counts and Compact inverted index.

Final training loop pseudocode

pre_token_counts = pre_tokenize(filepath)

for n_iters iterations:

# update self.pre_token_byte_counts in-place, while caching what's required

self.new_id = self.vocab_size

iter_merge_cached(self.pre_token_byte_counts)

left, right = self.convert(self.new_id)

self.vocab[self.new_id] = left+right

self.merges.append(updated_key)

Inference

During inference (encoding), merges are fixed and we don’t need to find the most frequent token anymore. The task is to apply rules greedily and efficiently. What’s the best data structure to store and apply the merges to our sequence?

I ended up using doubly linked list for the sequence of tokens for each word, so algorithm becomes:

-

- Split some batch of text and convert to bytes

-

- Encode each pre-token as a doubly-linked list of token ids.

-

- Scan for the highest-priority merge that matches; when you merge (x,y)→z, replace x with z and unlink y.

Finally, LeetCode is useful!!!

Additionally, since we don’t group pre-tokens into counts and instead stream tokenized outputs we lose speed. I applied LRU cache to fix that. We would cache results of input bytes so we don’t need to reapply merges again if we see the same pre-token again.

SuperBPE

After we trained tokenizer and spent so much time implementing it from scratch instead of just using huggingface tokenizers, we need to justify all of that time and train something more useful. Welcome SuperBPE.

SuperBPE is a fairly recent work, and in my opinion underexplored. When I sat implementing BPE from scratch I couldn’t get rid of an idea of this pre-tokenization. Why restrict ourselves to single words? Doing pre-tokens seems like a useful optimization hack, but language might not always work in words, but rather concepts? I could easily imagine cases where frequencies of multi-word spans can exceed those of adjacent byte-pairs. Language is redundant and contains phrases like “such as”, “to be considered”, “for example” which is logical to represent as a single token. SuperBPE solves exactly that. Now tokens can represent multiple words at once.

In order to implement SuperBPE, the only thing we need to change is our “pre_token_counts” representation. Instead of words going to each key, we could put a whole document there. It’s a huge dict, but the algorithm still works.

I tested it and consistently hit OOM, or my training would never finish (actually it’s the same problem as we started this blog post with). So I added a few heuristics: I split on punctuation; cap pre-token length at 10 tokens (only when a span exceeds 20 tokens), and apply few other heuristics + reduced dataset size.

Overview of SuperBPE

Final algorithm is still like 20x slower than my BPE implementation, but hopefully we don’t need to start from the beginning, as we could enable SuperBPE only at the last 20% of the training (this works better in practice, since we want for the BPE to learn general concepts inside words first (inter-word n-gram dependencies), and then lift this restriction)

Practical aspects

Okay, imagine you now have implemented a tokenizer that is so flexible it allows your custom way of training.

But

-

a) no one cares if it’s not supported in tokenizers

-

b) it’s still slow (it will require full Rust rewrite and perhaps for very large datasets will be slow)

So converting to tokenizers format to the rescue, turns out it’s not that hard!

After inspecting some open-source tokenizer vocabs (it’s stored inside tokenizer.json file) i noticed a few things:

- a) it’s serialized as json, but my vocab is stored in bytes (pickle).

I tried converting bytes to str, and that’s the whole point of Byte Level BPE - you cannot convert it to UTF-8 easily 😄

- b) HF uses some interesting choice of mapping bytes to some obscure UTF-8 characters. Whitespace becomes

Ġ,\nbecomesĊ

Turns out this was one of the quirks of Hugging Face’s tokenizers inherited from the original GPT-2 implementation by OpenAI.

In the GPT-2 tokenizer, every byte (0–255) is mapped to a unique, printable Unicode character so that text can be handled as normal strings in Python without losing byte information. They are chosen so that they are not used in typical English text.

TLDR;

"Ġhello"represents" hello".

This convention is purely aesthetic but became de-facto standard since GPT-2.

HF transformers have some example scripts to adapt pickle based vocab and merges to JSON, so it’s not hard to write your own script.

Experiments

The most interesting part.

I first trained my BPE implementation on good quality data from DCLM dataset. (About 500M tokens or 5 GB text file). I used an improved regex template with digit grouping and better splitting. My CPU is Ryzen 5

- Finished training in 38,562.8 s.

- Average iteration time: 0.764 s.

- Total sort time was 17,350.43 s.

It achieved compression ratio: 4.39 bytes per token

Tokenization speed on a full 12 GB file: 1193.2s -> 10.3 MB/s

SuperBPE is trained by resuming the basic BPE run from 26,000th iteration (roughly 80% of training).

-

Finished training in 53 hours

-

Sort time is 49% of it

!!! It’s 20x slower, let’s see if it’s worth it

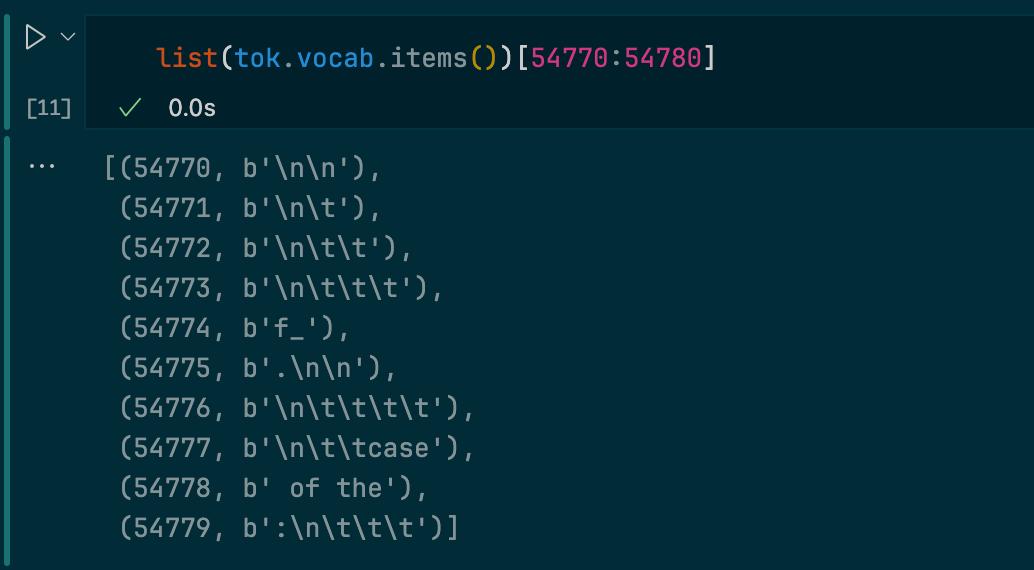

We could inspect vocab of SuperBPE to see that it’s indeed merged some whitespaces together into a single token or some phrases or code constructions. (screenshot is from the other experiment on slightly larger data and larger vocab)

|

|

|---|

LLM Training

I have used my baseline implementation of LLM training with hand-written Triton FlashAttention-2 and some tweaks.

Just trained a 70M-param LLM to <20 perplexity on DCLM in 5 hours – on a single consumer GPU.

— George Grigorev (@iamgrigorev) October 5, 2025

All my convergence + sample-efficiency tricks are stacking beautifully.

I now have separate repo with my research related to sample efficient GPT training, link in reply.

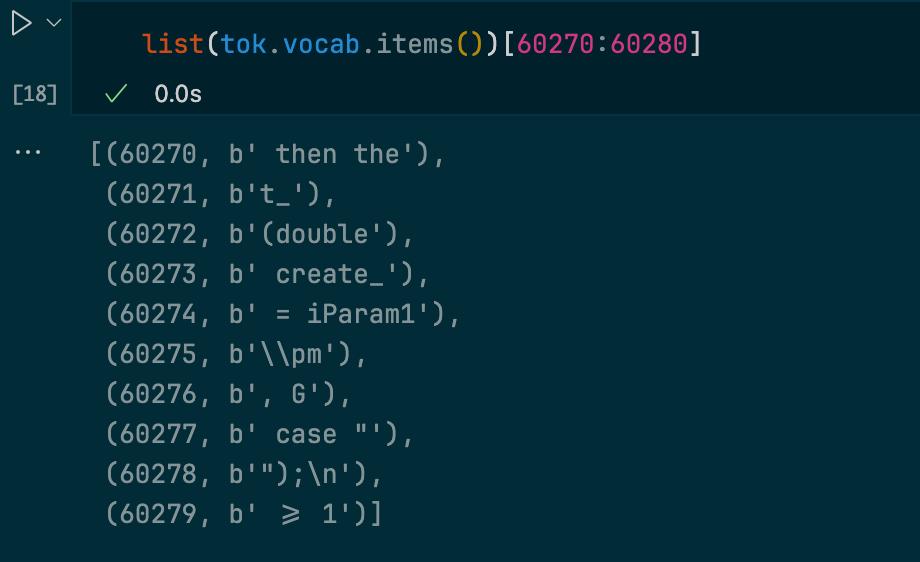

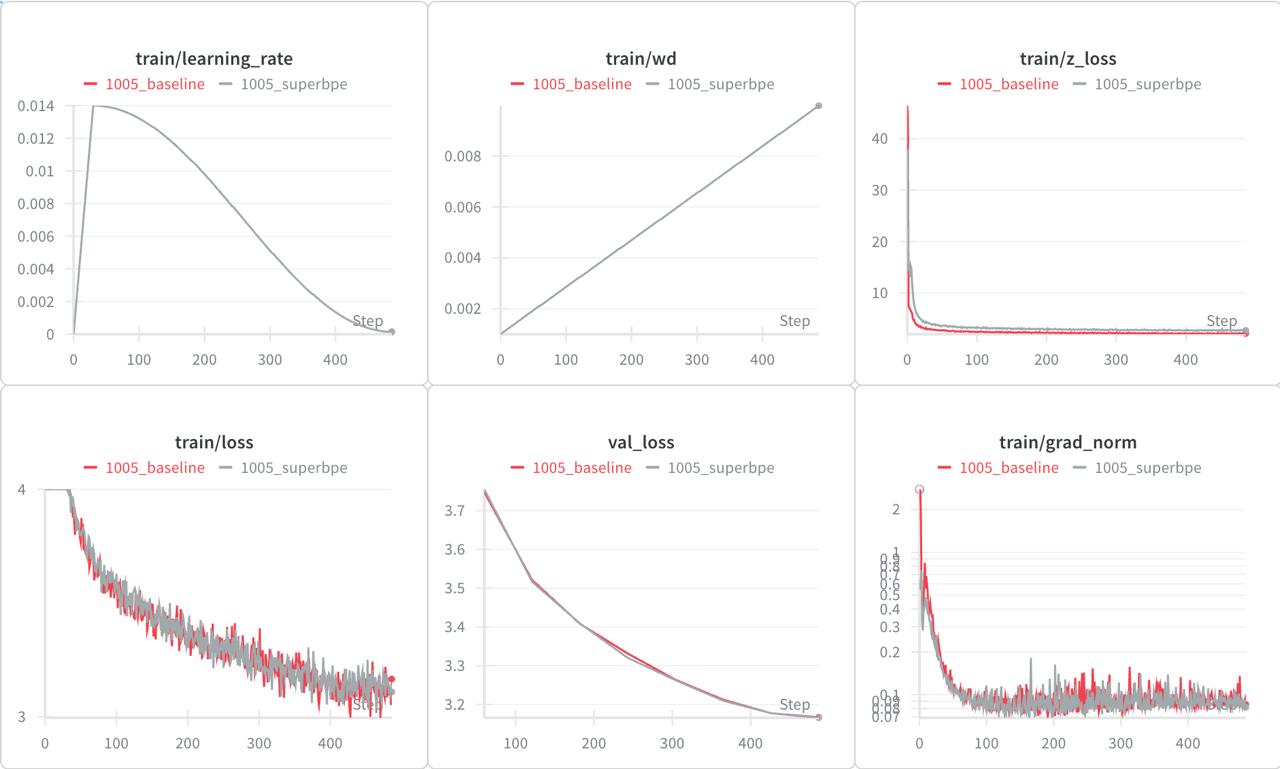

Two tokenizers trained with 32700 vocab size: “baseline BPE tokenizer” and “SuperBPE” tokenizer

Dataset used: DCLM (edu subset, filtered with score > 2.75) Token count: ~1.2B (24k iterations, 512 context length, 96 batch size, single GPU – RTX5090) Model vocab size: 32768 (multiple of 16 for better GPU utilization)

Non-embedding parameter count: 70M

After SuperBPE, dataset has 20% fewer tokens, so training is 20% more sample-efficient!

This matches results from the paper authors:

Super excited to see @moondream_ai's newest model use SuperBPE!! We did a little bit of analysis — using SuperBPE reduced their seqlen by 21% on average and made the token frequency distribution more uniform, meaning fewer hyper-frequent & hyper-rare tokens! https://t.co/6ZWNYWPOyx pic.twitter.com/KIk3gL5lvs

— Alisa Liu @ COLM 🦙 (@alisawuffles) September 29, 2025

Let’s now analyze tokens that are produced in SuperBPE:

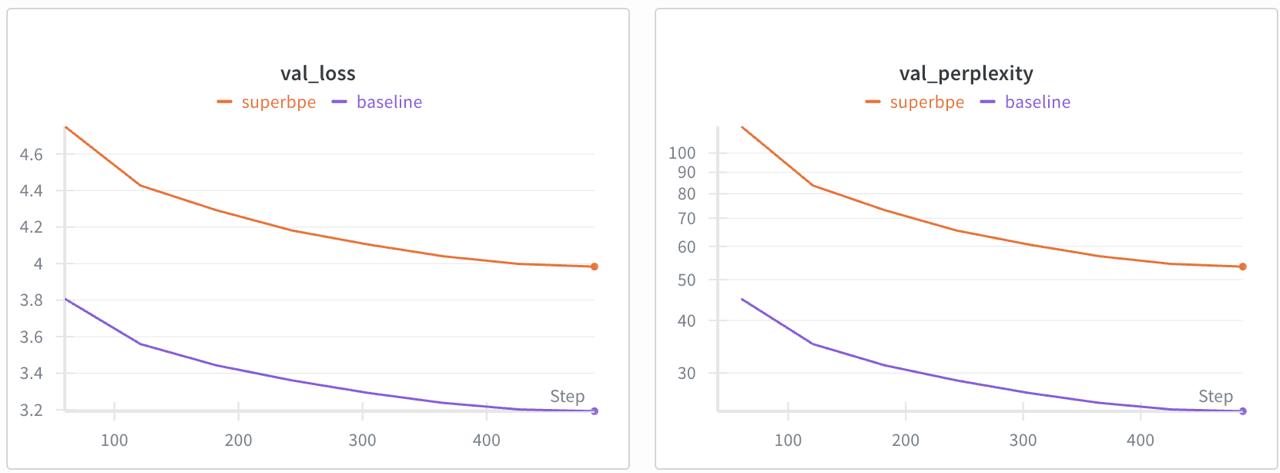

I run training using optimal settings with Muon optimizer for 2D params and AdamW for 1D params and here’s my loss results for training:

First run

After running first experiment, I noticed significantly higher loss. Then I checked outputs, it looked great, subjectively even better than the baseline. Something is wrong! What’s suspicious is that val loss is exactly 25% higher (3.19 -> 3.98). A-ha! Since each token now covers ~25% more text (because 1/(1-0.2)=1.25) and the model’s per-byte compression didn’t change, the per-token NLL (negative log-likelihood) should rise by that same 1.25x factor.

I calculated train/val loss multipliers by comparing dataset lengths in tokens and re-run experiments.

Loss scaled run

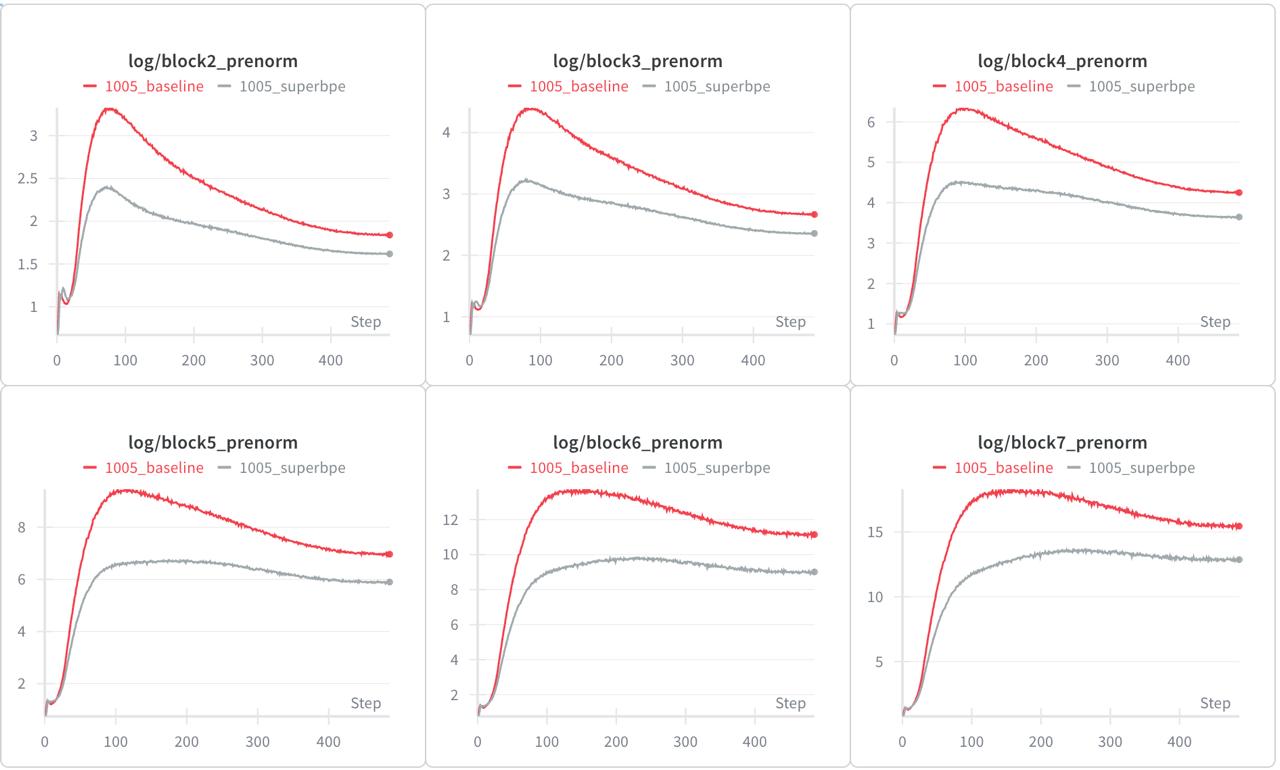

Interesting, we are seeing identical plots. However, SuperBPE shows slightly lower grad-norm and pre-activation norms!

Pre-activation norms

Considering that during generation your model should now produce 20% less tokens, validation loss is the same as the baseline, and lower norms, we could call SuperBPE tokens bring more regularization, and consider this method a free lunch!

I ran some generations using both models, using temperature=0.8 and top_p=0.8 on prompts taken from test set.

| # | Tokenizer | N tokens | Generated Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BPE | 41 | Sacramento, California Sacramento is the capital of the state of California, 13th largest city in the United States. It is the largest city in the state of California. |

| 2 | SuperBPE | 75 | Sacramento, California Sacramento is the capital of the state of California, 29 miles (50 km) southwest of San Francisco. Sacramento is situated in the southern part of the state, in the Sierras del Norte mountain range, between Sacramento and the Sierra Nevada mountain range. The state has a population of 14,069,403 (July 2010 est.). |

| 3 | BPE | 139 | What is Clostridium Botulinum? Clostridium Botulinum is a gram negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is most often found in the digestive tract of animals and humans. Clostridium Botulinum is also found in the human gut. What is the treatment for Clostridium Botulinum? The most common treatment for Clostridium Botulinum is a dose of Clostridium Botulinum injection. This is done under the supervision of a doctor. What is the prognosis for Clostridium Botulinum? Clostridium Botulinum is a life-threatening infection that can be fatal. |

| 4 | SuperBPE | 93 | What is Clostridium Botulinum? The Clostridium Botulinum is a Gram-positive, motile, spore-forming, anaerobic bacterium. It is able to live on various substrates, including dead plant tissue, organic matter, dead animals, and living organisms. It is a zoonotic organism which lives in soil and under aquatic plants. It usually occurs on soil surfaces or on surfaces that are exposed to direct sunlight, moisture, chemicals, or microbial activity. |

| 5 | BPE | 17 | Old age related health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure. |

| 6 | SuperBPE | 35 | Old age related health problems are more common in older adults than younger people. In addition, older adults with diabetes are also more likely to have higher blood pressure, stroke, heart disease, kidney disease, and certain types of cancer. |

BPE mistakes:

#1 is factually wrong (not 13th largest, not largest in CA)

#3 is factually wrong (not gram negative, but gram positive)

SuperBPE mistakes:

#2 - Geography wrong (it’s northeast, not southwest)

SuperBPE is more stable, coherent and factual, and uses less tokens.

Conclusion

Reimplementing BPE from first principles clarified how every design choice — regex patterns, caches, merge order, or data structures — affects efficiency.

SuperBPE extends this further, proving that smarter merge boundaries can deliver measurable gains in sample efficiency without compromising loss. It has it’s own drawbacks, particularly related to Evaluation (multiple choice answer is harder)

I had a lot of fun covering all the details and running experiments. Stay tuned for more!